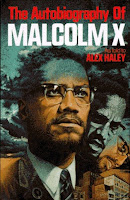

For years I have been assigning portions of the classic Autobiography of Malcolm X, as told to Alex Haley, to my Theoretical Criminology students. Whenever we discussed race and crime, and the prison industrial complex, we came back to the prison as a locus of political rebirth and resistance, and the Autobiography provided a convenient literary vehicle to start the discussion. I feel deeply enriched by this new, inclusive and fascinating volume, which sheds light from multiple perspectives on Malcolm X's life, and particuarly for illuminating corners that the Autobiography has missed.

Manning Marable, who sadly passed away from grave illness days before the biography was finished, spent years reading countless archival materials and interviewing important figures in Malcolm's life to provide us with a complicated picture of the man and his ideology. As the title suggests, Marable's narrative organizes Malcolm's life around the numerous transformations of his worldview and image.

Some of the focus on the book has related to Marable's revelations about Malcolm's personal life, which provide much more detail and accuracy than in the Autobiography. The book lays out a rich introduction about Malcolm's family, his father's murder, and the ways in which his childhood experience had shaped his political thinking. Even in the years preceding his conversion to Black Islam, he was not an apolitical man living in an intellectual vacuum; rather, even his early thinking was heavily influenced by the Garveyism with which he grew up. Of special interest to readers of thsi blog will be Marable's account of Malcolm's career in crime, which apparently was significantly aggrandized for rhetorical purposes. Marable does not shy from details about Malcolm's intimate life and relationships, with particular emphasis on his trouble marriage to Betty Shabazz. It is this part of the book, presumably, that led his daughter, Ilyasah, to resent the publication to the point of giving this agitated interview to NPR. But I find those details less of interest, except to the extent that they illustrate what should be obvious: that the pop culture icon is but one facet of a complicated man, with virtues and flaws, like the rest of us. To me, that does not make Malcolm's life's work any less revolutionary and astounding. What is more interesting, politically and ideologically, is the astounding series of transformations Malcolm went through, cut short by his tragic assassination.

Marable's account of Malcolm's career in the Nation of Islam highlights the complexities of working within a deeply hierarchical organization. A nuanced analysis of Malcolm's speeches during this time, including the infamous "chickens come home to roost" comment (finally put in context) reveals his struggle between being his own person and his loyalty to Elijah Muhammad. It also reveals the inner workings of the organization, complete with power plays at the different Mosques and at the Chicago headquarters, and the ways in which Malcolm's charisma and quick ascension to power frightened the people who initially nurtured and revered him. Similarly, the book shows the unraveling of Malcolm's relationship with Muhammad and the process of his ousting from the Nation of Islam as a mix of ideological and ethical issues. Previous accounts of the unraveling of Malcolm's relationship with Nation of Islam have focused on his disgust with Elijah Muhammad's sexual escapades and his treatment of his numerous mistresses and illegitimate children, but have glossed over Malcolm's gradual understanding of the serious flaws in a program of Black separatism and apolitical stance. Marable provides blow-by-blow accounts of Malcolm's debates on the media with civil rights advocates, particularly Bayard Rustin, exposing the strengths and weaknesses in Malcolm's program. Beyond the personal and ethical issues he might have had with Muhammad's personality or with the Nation of Islam's theology (to which he was gradually exposed as he became better acquainted with mainstream Sunni Islam), these accounts show that his parting from the Nation was a natural consequence from his growing understanding that political action was essential.

Particularly precious are Marable's detailed accounts of Malcolm's trips to Africa and the Middle East. Relying on numerous interviews, letters and Malcolm's own journal, we see him go through a series of intellectual transformations, embracing racial inclusiveness, and coming to see the challenges of race in America through the prism of international human rights. This progression of ideas was too quick-paced for Haley to be able to fully capture in a book written and published in 1965, but from the vantage point of later times we are able to appreciate that Malcolm was still undergoing important ideological and spiritual changes as he was struggling to construct a platform for activism. These changes - particularly his embrace of Pan-Africanism and universal Islam as detached from skin color, and his interest in presenting the case for American Blacks on the international stage - were naturally confusing to his followers, who remained behind when he was on his trips, and who were for the most part people who remembered him well from his Nation of Islam days and still embraced, at least partly, the old ideology. This phase of confusion, which was never fully over, was enhanced by the tensions between Malcolm's two post-Nation-of-Islam organizations: Muslim Mosque, Inc., and the secular, human-rights oriented Organization of Afro-American Unity. Marable aims at sketching some possible directions that these organizations might have taken if not for Malcolm's death.

Finally, the book provides a prism of perspectives on the assassination, strongly suggesting that the wrong people were apprehended and pointing at some directions to reveal the full assassination plot that have not been adequately investigated; it was Marable's hope that the book would lead to a reopening of the murder investigation.

How does Marable's book change the experience of reading the Autobiography? As Marable himself points out, the best way to read and appreciate the Autobiography is as a memoir rather than a work of documented truth. Readers of the Autobiography are advised to keep in mind that Haley was not without his own perspective on Malcolm, and that both he and Malcolm had important agendas when creating the Autobiography. It is also important to keep in mind the timing of the Autobiography's publication, which explains why the fascinating transformations that followed Malcolm's departure from Nation of Islam are left, for the most part, without serious treatment in the Autobiography. I think that reading the two books as companions provides a thoroughly rich experience, one that does justice to an important and enigmatic leader whose legacy informs many of the struggles we still face today, including the struggle near and dear to our readers' hearts--the struggle for social and racial justice in the context of mass incarceration.

Thoughts and News on Criminal Justice and Correctional Policy in California

Saturday, June 30, 2012

Tuesday, June 26, 2012

County Sherrifs Allowed to Release Terminally Ill Inmates

SB 1462, proposed by Mark Leno, passed today in the Senate. It authorizes sheriffs to release inmates from county jail for transfer to a hospital or a hospice, upon the advice of a physician, if the inmate is deemed to have a life expectancy of six months or less and is not a danger to public safety. The bill states that, for inmates eligible for Medi-Cal, the county will continue to pay the nonfederal share of the costs after release.

This is one more block in the general trend of paying close attention to elderly and infirm patients, such as geriatric parole. One of the major features of doing selective incapacitation on a budget is that we still classify people into groups, but now the groups are arranged based on cost, not just risk.

This is one more block in the general trend of paying close attention to elderly and infirm patients, such as geriatric parole. One of the major features of doing selective incapacitation on a budget is that we still classify people into groups, but now the groups are arranged based on cost, not just risk.

Monday, June 25, 2012

MORE BREAKING NEWS: Supreme Court Strikes Down Portions of Arizona Anti-Immigration Bill

|

| SB1070 protest poster, courtesy NuevaRaza |

In Arizona et al. v. United States, the Opinion of the Court, by Justice Kennedy, held that Congress gave the Federal Government's power over regulating immigration. This authorization has preempted state law, and therefore does not leave room for states to legislate on this matter. Several provisions of SB1070, therefore, violate the Supremacy Clause.

The first problematic section, Section 3, set up a state registration program, violating the intent for the Federal plan to be a "single integrated and all embracing system."

Another problematic section, 5(c), which made it a crime for an undocumented alien to be employed by the State of Arizona, violates the federal scheme, which criminalized employees for employing "illegal aliens", but not the aliens themselves.

Section 6, which is most of concern to criminal justice enthusiasts, allowed local police officers to make warrantless arrests of certain aliens suspected of being removable. The Supreme Court unequivocally states that it is not a crime, generally, for a removable alien to remain in the United States, and it is only at specific stages of the removal process that there is authorization for arrest, such as when the alien is "likely to escape before a warrant can be obtained." The state system is not the one created by congress, and thus violates the Supremacy Clause.

It is important to state, however, that section 2(b) has remained intact. It allows for mandatory checks and has some limitations (such as the presentation of a valid AZ driver's license and the prohibition on racial profiling.) According to the Supreme Court, enjoining that section is premature, as it is not yet clear whether local police will enforce it in a discriminatory fashion, or detain people for longer than required to check their immigration status.

BREAKING NEWS: Supreme Court Rules Life Without Parole for Juveniles Unconstitutional

|

| Evan Miller. Image courtesy The North Star News. |

The Opinion of the Court, written by Justice Kagan, relies on prior case law - particularly Roper v. Simmons and Graham v. Florida - to delineate the differences between juveniles and adults, particularly their less-formed character and vulnerability to outside influences. While Graham addressed crimes other than murder, its statements about children's development was not crime-specific. Reliance on the discretion of prosecutors, wrote Justice Kagan, is not enough, as many states have mandatory sentencing schemes that require life without parole.

I would like to draw your attention to two important points regarding the Court's decision, which work at cross purposes. On one hand, much of the Graham v. Florida discussion draws a comparison between life without parole and the death penalty. This is a powerful hook that could serve, sometime in the future, as an attempt to abolish life without parole, after we have abolished the death penalty. On the other hand, the case relies heavily on the differentiation between children and adults, which might hinder a delegitimization of life without parole for adults.

Tuesday, June 12, 2012

Three Strikes Reform Initiative Approved for Ballot

The initiative to allow voters to reform the Three Strikes Law has qualified to be on the 2012 California ballot.

What is this about? The full text of the initiative is here, and as a careful read will show, this offers considerably less than ardent activists against mass incarceration would hope for. The opening, as is customary in anti-punitive proposals, reads as being extremely punitive, and the rhetoric is so dense that it's hard to read through it. But let's give it a try. Here are the main premises of the proposed act:

Third-strikers will come in two varieties: Minor and major third-strikers.

Minor third-strikers - that is, folks with two prior serious/violent offenses but a third nonserious/nonviolent offense - will receive double the sentence, in lieu of 25 years to life.

Major third-strikers - that is, folks whose third offense is serious/violent, will still receive 25 years to life.

Even if your last offense is nonserious/nonviolent, you will be sentenced as a major third-striker if one or more of your prior strikes was a sex offense, a homicide, certain narcotics offenses, assault on a police officer, and a few other exceptions.

The time between convictions will still not make a difference.

Second strikers' fate will not change. Second strikers with a serious felony (following conviction of a serious felony) will get a five-year sentence enhancement, unless the situation is covered by a greater enhancement statute. The time that passed between the convictions does not matter, and the sentence will be served at a state prison.

Resentencing: Third strikers sentenced to life for a third nonviolent/nonserious offense under the old law will be allowed to submit a petition for resentencing within two years from the law's passage. Anyone else (third strikers in prison for violent third strikes, second strikers) cannot benefit from this provision.

As with everything, there's a prominent financial angle. The initiative's website promotes immense budget savings and links to this report, which highlights the budgetary strain by elderly and infirm inmates such as three-strikers.

The formulation of this proposition raises a few questions. First, is this enough? It'll certainly prevent travesties such as sentencing pizza thieves to life, but it maintains three strikes for all other offenders. Despite the language preventing prosecutors from plea bargaining, there is still wiggle room, and folks with certain violent or sex convictions in their history--regardless of how long it's been since then--will not benefit from this modification.

Second, will the public safety and fiscal prudence veneer be enough to convince centrist voters that this is a good idea? I doubt that staunch Three Strikes supporters will buy into the "dangerous criminals are released because pizza thieves are serving life sentences" rhetoric. Back in 1994, voters could have approved a more lenient version of Three Strikes; four or five of those were on the table. They chose to vote for the most punitive one they were offered. Centrists, however, might be persuaded to support this initiative if they take the trouble to read it. It'll convince them that it covers a fairly small number of cases and retains the draconic punishment structure for a variety of situations. This might be cause for calm for some voters, and cause for dismay for those supporting broader reforms.

Third, what about the advertised huge savings? The Legislative Analyst's Office report on the initiative answers that in the affirmative, estimating savings for the state system in the $100 million range. However, it also mentions that costs for local government and jails may increase by millions to tens-of-millions, albeit those costs may decrease.

What is this about? The full text of the initiative is here, and as a careful read will show, this offers considerably less than ardent activists against mass incarceration would hope for. The opening, as is customary in anti-punitive proposals, reads as being extremely punitive, and the rhetoric is so dense that it's hard to read through it. But let's give it a try. Here are the main premises of the proposed act:

Third-strikers will come in two varieties: Minor and major third-strikers.

Minor third-strikers - that is, folks with two prior serious/violent offenses but a third nonserious/nonviolent offense - will receive double the sentence, in lieu of 25 years to life.

Major third-strikers - that is, folks whose third offense is serious/violent, will still receive 25 years to life.

Even if your last offense is nonserious/nonviolent, you will be sentenced as a major third-striker if one or more of your prior strikes was a sex offense, a homicide, certain narcotics offenses, assault on a police officer, and a few other exceptions.

The time between convictions will still not make a difference.

Second strikers' fate will not change. Second strikers with a serious felony (following conviction of a serious felony) will get a five-year sentence enhancement, unless the situation is covered by a greater enhancement statute. The time that passed between the convictions does not matter, and the sentence will be served at a state prison.

Resentencing: Third strikers sentenced to life for a third nonviolent/nonserious offense under the old law will be allowed to submit a petition for resentencing within two years from the law's passage. Anyone else (third strikers in prison for violent third strikes, second strikers) cannot benefit from this provision.

As with everything, there's a prominent financial angle. The initiative's website promotes immense budget savings and links to this report, which highlights the budgetary strain by elderly and infirm inmates such as three-strikers.

The formulation of this proposition raises a few questions. First, is this enough? It'll certainly prevent travesties such as sentencing pizza thieves to life, but it maintains three strikes for all other offenders. Despite the language preventing prosecutors from plea bargaining, there is still wiggle room, and folks with certain violent or sex convictions in their history--regardless of how long it's been since then--will not benefit from this modification.

Second, will the public safety and fiscal prudence veneer be enough to convince centrist voters that this is a good idea? I doubt that staunch Three Strikes supporters will buy into the "dangerous criminals are released because pizza thieves are serving life sentences" rhetoric. Back in 1994, voters could have approved a more lenient version of Three Strikes; four or five of those were on the table. They chose to vote for the most punitive one they were offered. Centrists, however, might be persuaded to support this initiative if they take the trouble to read it. It'll convince them that it covers a fairly small number of cases and retains the draconic punishment structure for a variety of situations. This might be cause for calm for some voters, and cause for dismay for those supporting broader reforms.

Third, what about the advertised huge savings? The Legislative Analyst's Office report on the initiative answers that in the affirmative, estimating savings for the state system in the $100 million range. However, it also mentions that costs for local government and jails may increase by millions to tens-of-millions, albeit those costs may decrease.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)