According to media reports, California state prisoners are killed at a rate that doubles the national average [update: I'm not sure this is true, having looked at the numbers more recently]. A sensible proposition has been made--and rejected: The Merced Sun-Star reports:

The department will not reinstate a policy dropped 15 years ago that required potential sensitive needs cellmates to fill out a compatibility form before they are housed together, Ralph Diaz, acting deputy director for adult institutions, told a Senate budget subcommittee.

Sex offenders, former gang members and other vulnerable inmates are placed in special sensitive needs housing for their protection.

However, the inspector general and an analysis by The Associated Press published in February found that a disproportionate number of homicide victims were sensitive needs inmates.

The compatibility forms help officials assess whether inmates can live peacefully together. They are required for inmates housed together in other segregated living units, and Sen. Loni Hancock said they should be required for sensitive needs inmates as well.

"We do look for inmates who we feel should not be celling with others," Diaz testified. However, he said using the forms for sensitive needs and general population inmates would be too cumbersome and the department's current process can appropriately address housing concerns.

There are two ways of viewing this debate. One is through the usual old-skool impasse between carceral discourse and rights discourse. The other, however, is cost-oriented. CDCR is refusing to reinstate this policy because it believes that it would needlessly complicate its operations; Senator Hancock thinks that the costs in lives and healthcare offset these considerations.

This debate is an example of a situation in which a prison is not really sui generis. In any other setting, in which people are thrown together--especially in total institutions--it's best if they spend time in close quarters with people with whom they can get along. This is not merely a matter of finding the roomie's company enjoyable; it's about preventing exploitation, abuse, and conflict.

Thoughts and News on Criminal Justice and Correctional Policy in California

Friday, April 24, 2015

Saturday, April 18, 2015

Death Penalty Debate in an Abolitionist State

With Dzhokhar Tsarnaev convicted of all 30 counts (among them four dead and 260 wounded victims), the federal trial of the Boston Marathon bomber has now entered the sentencing phase. This phase is estimated to take four weeks. It has been fascinating to follow the debate about the death penalty, which, while legal because of the federal setting, is taking place in Massachusetts, an abolitionist state.

After Gregg v. Georgia enabled states to recreate their death penalty statutes, Massachusetts reinstated the death penalty for first-degree murders. However, in Comm. v. Colon-Cruz, this statute was ruled unconstitutional, because it discriminated between defendants who pled guilty and defendants who went trial (this, by the way, is interesting; after all, the prosecution regularly offers to take the death penalty of the table in retentionist states for a guilty plea). A few governors, including Mitt Romney, tried to reinstate the death penalty with no success; in a 2004 report to then-governor Romney, a commission recommended that "any death penalty statute that may be considered in Massachusetts would be as narrow, and as foolproof, as possible."

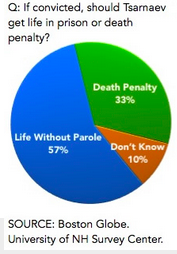

As is often the case in abolitionist states (and countries) public opinion lagged behind the legal change. Death Penalty Info cites a Boston Globe story from April 2003, according to which a poll conducted at the time found that 53% respondents supported capital punishment against 41% opposed to the practice. This was a significant decline from a 1996 poll, which found 65% in favor of the death penalty and only 26% opposed. But a recent poll, asking, "If convicted, should Tsarnaev get life in prison or the death penalty?" produced 57% supporting life without parole and only 33% supporting the death penalty.

Interestingly, the editorials calling to spare Tsarnaev all raise an important argument that is typically absent from California capital cases: the need to relegate Tsarnaev to the shadows, rather than make him a martyr whose case will make the news every time an execution date is set. Ironically, it is in this "obvious case" that, specifically because of the hate motive, there is hesitation in creating the media and litigation hoopla that would accompany a capital sentence. Yesterday, the New York Times reported that the parents of Tsarnaev's youngest victim, 8-year-old Martin Richard, have asked the prosecution not to ask for the death penalty for a similar reason:

“As long as the defendant is in the spotlight, we have no choice but to live a story told on his terms, not ours,” they wrote. “The minute the defendant fades from our newspapers and TV screens is the minute we begin the process of rebuilding our lives and our family.”

This argument is particularly interesting for us in retentionist California. In a place like Massachusetts, in which the death penalty is unusual and only on the table because of the federal setting, an argument about the risk of martyrdom makes a lot of sense. Where death sentences are commonplace, however, it's less likely to succeed. Ironically, while this argument can help mass murderers with hate motives, it has less potential for single-victim murderers and less publicized cases. Moreover, it does not characterize the debate in retentionist states.

In 1971, a California jury sentenced Charles Manson, Patricia Krenwinkel, Leslie van Houten and Susan Atkins to death for the murders of seven victims. Because of the death penalty (temporary) abolition in 1972, their sentences were commuted to life, which meant, in those days, that they all came before the parole board as soon as 1978. Susan Atkins died in 2009. Patricia Krenwinkel, the subject of a new short documentary, is the longest-serving female inmate in California. Prosecutor Vincent Bugliosi's memoir of the trial written with Curt Gentry, Helter Skelter, makes no mention of any martyrdom considerations or, really, any reservation he had in asking for the death penalty.

This comparison, among others, makes me think that death penalty abolition does not only change support and opposition rates: it also changes the nature of the debate. We tend to forget that, because we don't usually hold capital punishment polls in abolitionist states. By contrast, the debate in retentionist states has reached an impasse that makes it extremely shallow. Either we focus on "tinkering to the machinery of death" or we try to abolish it for cost reasons. Places that are not confronted with the daily realities of an in-state death row allow their residents not only freedom from the moral discomforts that come with its application, but also the freedom to infuse their opinions on the subject with philosophical considerations. Abolition, therefore, makes us morally richer not only directly, but also in intangible ways.

After Gregg v. Georgia enabled states to recreate their death penalty statutes, Massachusetts reinstated the death penalty for first-degree murders. However, in Comm. v. Colon-Cruz, this statute was ruled unconstitutional, because it discriminated between defendants who pled guilty and defendants who went trial (this, by the way, is interesting; after all, the prosecution regularly offers to take the death penalty of the table in retentionist states for a guilty plea). A few governors, including Mitt Romney, tried to reinstate the death penalty with no success; in a 2004 report to then-governor Romney, a commission recommended that "any death penalty statute that may be considered in Massachusetts would be as narrow, and as foolproof, as possible."

As is often the case in abolitionist states (and countries) public opinion lagged behind the legal change. Death Penalty Info cites a Boston Globe story from April 2003, according to which a poll conducted at the time found that 53% respondents supported capital punishment against 41% opposed to the practice. This was a significant decline from a 1996 poll, which found 65% in favor of the death penalty and only 26% opposed. But a recent poll, asking, "If convicted, should Tsarnaev get life in prison or the death penalty?" produced 57% supporting life without parole and only 33% supporting the death penalty.

Interestingly, the editorials calling to spare Tsarnaev all raise an important argument that is typically absent from California capital cases: the need to relegate Tsarnaev to the shadows, rather than make him a martyr whose case will make the news every time an execution date is set. Ironically, it is in this "obvious case" that, specifically because of the hate motive, there is hesitation in creating the media and litigation hoopla that would accompany a capital sentence. Yesterday, the New York Times reported that the parents of Tsarnaev's youngest victim, 8-year-old Martin Richard, have asked the prosecution not to ask for the death penalty for a similar reason:

“As long as the defendant is in the spotlight, we have no choice but to live a story told on his terms, not ours,” they wrote. “The minute the defendant fades from our newspapers and TV screens is the minute we begin the process of rebuilding our lives and our family.”

This argument is particularly interesting for us in retentionist California. In a place like Massachusetts, in which the death penalty is unusual and only on the table because of the federal setting, an argument about the risk of martyrdom makes a lot of sense. Where death sentences are commonplace, however, it's less likely to succeed. Ironically, while this argument can help mass murderers with hate motives, it has less potential for single-victim murderers and less publicized cases. Moreover, it does not characterize the debate in retentionist states.

In 1971, a California jury sentenced Charles Manson, Patricia Krenwinkel, Leslie van Houten and Susan Atkins to death for the murders of seven victims. Because of the death penalty (temporary) abolition in 1972, their sentences were commuted to life, which meant, in those days, that they all came before the parole board as soon as 1978. Susan Atkins died in 2009. Patricia Krenwinkel, the subject of a new short documentary, is the longest-serving female inmate in California. Prosecutor Vincent Bugliosi's memoir of the trial written with Curt Gentry, Helter Skelter, makes no mention of any martyrdom considerations or, really, any reservation he had in asking for the death penalty.

This comparison, among others, makes me think that death penalty abolition does not only change support and opposition rates: it also changes the nature of the debate. We tend to forget that, because we don't usually hold capital punishment polls in abolitionist states. By contrast, the debate in retentionist states has reached an impasse that makes it extremely shallow. Either we focus on "tinkering to the machinery of death" or we try to abolish it for cost reasons. Places that are not confronted with the daily realities of an in-state death row allow their residents not only freedom from the moral discomforts that come with its application, but also the freedom to infuse their opinions on the subject with philosophical considerations. Abolition, therefore, makes us morally richer not only directly, but also in intangible ways.

Tuesday, April 7, 2015

Homicide on Video: What Is It Going to Take?

Here is the unedited footage of the shooting of Walter Scott in South Carolina, three days ago.

I have now watched the clip three times--almost as many times as I watched the footage of Oscar Grant's killing, and of Eric Garner's killing, and of countless others. I am having a hard time seeing it as anything but murder, with a bloodcurdling effort to cover the murderer's tracks after the fact. Then again, when I had watched the video of Oscar Grant's killing, and of Eric Garner's killing, and of countless others, those were also hard to interpret as anything but murder, and each of those times ended in what I can only describe as absolute legal impotence, and each of those times I've looked at my screen, incredulous, thinking, "what more could you possibly want/expect to see before you called this what it is?"

I am trying to imagine how this footage can be interpreted in a different way--what sort of teary-eyed testimony the cop might give in his own defense--and how a rational jury could possibly interpret this footage as anything but murder. I am trying to get into the head of the cop's defense attorney, to think how he can possibly describe this footage in a different way. I can't even imagine such a scenario. But you know what? I had the exact same thoughts when I saw Eric Garner's killing, and we all know how *that* turned out. It seems like the evidence is getting better and better, but the results are not, and we are fast losing hope that there is such a thing as "perfect" video footage of murder.

Ask yourself, gentle reader: all those other times you saw unspeakable horror on video, did you not say to yourself, as I did, this time it's the ultimate evidence? This time the evildoer won't get away? What makes us think that this one, this last one, will be different? That this time someone has finally managed to catch indefensible evil on tape? That this one won't be a hung jury or some involuntary manslaughter or somesuch? And if this one isn't, what more could "they" possibly need to see what we see? What, if not this--if not Eric Garner--if not Tamir Rice--if not any number of videos we've seen--is going to be incontrovertible evidence of murder? Will there ever be incontrovertible evidence? What, for Heaven's sake, is it going to take?

My heart is with the many sad and angry people in South Carolina who are trying to make sense of it, some of whom may have just realized that Ferguson is not a place, it is a state of consciousness. Yes, black lives matter. They should matter. But until all lives matter equally, none of us should feel calm, or safe, or contented.

The screaming, struggling civilian was a dark man with a face white as flour from fear. His eyes were pulsating in hectic desperation, flapping like bat’s wings, as the many tall policemen seized him by the arms and legs and lifted him up. His books were spilled on the ground. “Help!” he shrieked shrilly in a voice strangling in its own emotion, as the policemen carried him to the open doors in the rear of the ambulance and threw him inside. “Police! Help! Police!” The doors were shut and bolted, and the ambulance raced away. There was a humorless irony in the ludicrous panic of the man screaming for help to the police while policemen were all around him. Yossarian smiled wryly at the futile and ridiculous cry for aid, then saw with a start that the words were ambiguous, realized with alarm that they were not, perhaps, intended as a call for police but as a heroic warning from the grave by a doomed friend to everyone who was not a policeman with a club and a gun and a mob of other policemen with clubs and guns to back him up. “Help! Police!” the man had cried, and he could have been shouting of danger.

--Joseph Heller, Catch-22

I have now watched the clip three times--almost as many times as I watched the footage of Oscar Grant's killing, and of Eric Garner's killing, and of countless others. I am having a hard time seeing it as anything but murder, with a bloodcurdling effort to cover the murderer's tracks after the fact. Then again, when I had watched the video of Oscar Grant's killing, and of Eric Garner's killing, and of countless others, those were also hard to interpret as anything but murder, and each of those times ended in what I can only describe as absolute legal impotence, and each of those times I've looked at my screen, incredulous, thinking, "what more could you possibly want/expect to see before you called this what it is?"

I am trying to imagine how this footage can be interpreted in a different way--what sort of teary-eyed testimony the cop might give in his own defense--and how a rational jury could possibly interpret this footage as anything but murder. I am trying to get into the head of the cop's defense attorney, to think how he can possibly describe this footage in a different way. I can't even imagine such a scenario. But you know what? I had the exact same thoughts when I saw Eric Garner's killing, and we all know how *that* turned out. It seems like the evidence is getting better and better, but the results are not, and we are fast losing hope that there is such a thing as "perfect" video footage of murder.

Ask yourself, gentle reader: all those other times you saw unspeakable horror on video, did you not say to yourself, as I did, this time it's the ultimate evidence? This time the evildoer won't get away? What makes us think that this one, this last one, will be different? That this time someone has finally managed to catch indefensible evil on tape? That this one won't be a hung jury or some involuntary manslaughter or somesuch? And if this one isn't, what more could "they" possibly need to see what we see? What, if not this--if not Eric Garner--if not Tamir Rice--if not any number of videos we've seen--is going to be incontrovertible evidence of murder? Will there ever be incontrovertible evidence? What, for Heaven's sake, is it going to take?

My heart is with the many sad and angry people in South Carolina who are trying to make sense of it, some of whom may have just realized that Ferguson is not a place, it is a state of consciousness. Yes, black lives matter. They should matter. But until all lives matter equally, none of us should feel calm, or safe, or contented.

The screaming, struggling civilian was a dark man with a face white as flour from fear. His eyes were pulsating in hectic desperation, flapping like bat’s wings, as the many tall policemen seized him by the arms and legs and lifted him up. His books were spilled on the ground. “Help!” he shrieked shrilly in a voice strangling in its own emotion, as the policemen carried him to the open doors in the rear of the ambulance and threw him inside. “Police! Help! Police!” The doors were shut and bolted, and the ambulance raced away. There was a humorless irony in the ludicrous panic of the man screaming for help to the police while policemen were all around him. Yossarian smiled wryly at the futile and ridiculous cry for aid, then saw with a start that the words were ambiguous, realized with alarm that they were not, perhaps, intended as a call for police but as a heroic warning from the grave by a doomed friend to everyone who was not a policeman with a club and a gun and a mob of other policemen with clubs and guns to back him up. “Help! Police!” the man had cried, and he could have been shouting of danger.

--Joseph Heller, Catch-22

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)