With Dzhokhar Tsarnaev convicted of all 30 counts (among them four dead and 260 wounded victims), the federal trial of the Boston Marathon bomber has now entered the sentencing phase. This phase is estimated to take four weeks. It has been fascinating to follow the debate about the death penalty, which, while legal because of the federal setting, is taking place in Massachusetts, an abolitionist state.

After Gregg v. Georgia enabled states to recreate their death penalty statutes, Massachusetts reinstated the death penalty for first-degree murders. However, in Comm. v. Colon-Cruz, this statute was ruled unconstitutional, because it discriminated between defendants who pled guilty and defendants who went trial (this, by the way, is interesting; after all, the prosecution regularly offers to take the death penalty of the table in retentionist states for a guilty plea). A few governors, including Mitt Romney, tried to reinstate the death penalty with no success; in a 2004 report to then-governor Romney, a commission recommended that "any death penalty statute that may be considered in Massachusetts would be as narrow, and as foolproof, as possible."

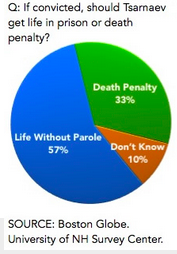

As is often the case in abolitionist states (and countries) public opinion lagged behind the legal change. Death Penalty Info cites a Boston Globe story from April 2003, according to which a poll conducted at the time found that 53% respondents supported capital punishment against 41% opposed to the practice. This was a significant decline from a 1996 poll, which found 65% in favor of the death penalty and only 26% opposed. But a recent poll, asking, "If convicted, should Tsarnaev get life in prison or the death penalty?" produced 57% supporting life without parole and only 33% supporting the death penalty.

Interestingly, the editorials calling to spare Tsarnaev all raise an important argument that is typically absent from California capital cases: the need to relegate Tsarnaev to the shadows, rather than make him a martyr whose case will make the news every time an execution date is set. Ironically, it is in this "obvious case" that, specifically because of the hate motive, there is hesitation in creating the media and litigation hoopla that would accompany a capital sentence. Yesterday, the New York Times reported that the parents of Tsarnaev's youngest victim, 8-year-old Martin Richard, have asked the prosecution not to ask for the death penalty for a similar reason:

“As long as the defendant is in the spotlight, we have no choice but to live a story told on his terms, not ours,” they wrote. “The minute the defendant fades from our newspapers and TV screens is the minute we begin the process of rebuilding our lives and our family.”

This argument is particularly interesting for us in retentionist California. In a place like Massachusetts, in which the death penalty is unusual and only on the table because of the federal setting, an argument about the risk of martyrdom makes a lot of sense. Where death sentences are commonplace, however, it's less likely to succeed. Ironically, while this argument can help mass murderers with hate motives, it has less potential for single-victim murderers and less publicized cases. Moreover, it does not characterize the debate in retentionist states.

In 1971, a California jury sentenced Charles Manson, Patricia Krenwinkel, Leslie van Houten and Susan Atkins to death for the murders of seven victims. Because of the death penalty (temporary) abolition in 1972, their sentences were commuted to life, which meant, in those days, that they all came before the parole board as soon as 1978. Susan Atkins died in 2009. Patricia Krenwinkel, the subject of a new short documentary, is the longest-serving female inmate in California. Prosecutor Vincent Bugliosi's memoir of the trial written with Curt Gentry, Helter Skelter, makes no mention of any martyrdom considerations or, really, any reservation he had in asking for the death penalty.

This comparison, among others, makes me think that death penalty abolition does not only change support and opposition rates: it also changes the nature of the debate. We tend to forget that, because we don't usually hold capital punishment polls in abolitionist states. By contrast, the debate in retentionist states has reached an impasse that makes it extremely shallow. Either we focus on "tinkering to the machinery of death" or we try to abolish it for cost reasons. Places that are not confronted with the daily realities of an in-state death row allow their residents not only freedom from the moral discomforts that come with its application, but also the freedom to infuse their opinions on the subject with philosophical considerations. Abolition, therefore, makes us morally richer not only directly, but also in intangible ways.

No comments:

Post a Comment