As I type this, thousands of Israeli Arab citizens, residents of Magd-al-Crum (an Arab town in the Upper Galilee) are protesting against the Israeli government's failure to appropriately address violence in Israeli Arab society. Ha'aretz reports:

The day before yesterday two brothers were fatally shot at the town in a browl, and today another young man who was badly injured in the fight, Muhammad Saba, died of his injuries. The protesters are calling out derogatory calls about the police and its crime-fighting abilities, including, "Ardan [the police minister], you're a coward", and bearing signs saying, "violence--not in our streets" and "living in peace is already a dream." Muhammad Baraka, the Chairman of the Supervision Committee for the Arab Population, said at the end of the march that, "if in Magd-al-Crum and [other] Arab towns there won't be peace--there won't be peace anywhere. It is not a threat, it is an elementary right for any citizen in a proper society.

Since the beginning of the year, more than 70 Arab Israeli citizens were murdered throughout the country. Among the marchers were thousands of villagers, as well as citizens from all over the country, mayors, Knesset members and religious leaders. Prominent at the rally were women, who wore black shirts for mourning, called out slogans and marched with their children who carried signs against violence. Even the family members of the two brothers who were murdered in the village, Halil and Ahmed Man'aa, attended the protest.

|

| Homicide victims per 100,000, by religion, 2014-2016 (non- Jews in red). |

|

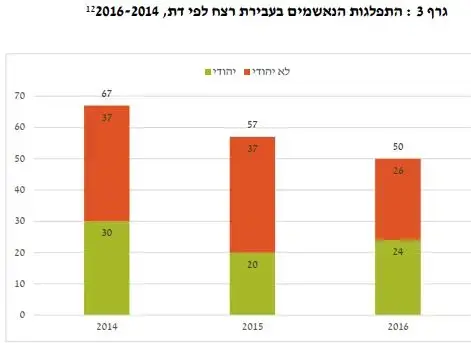

| Homicide defendants by religion, 2014-2016 (non-Jews in red). |

The graphs from the report prove the point. Arab Israelis, who constitute about 20% of the Israeli population, are responsible for more than 50% of homicide offenses per annum. This is not the fabricated, misleading product of overenforcement or targeting by Israeli police (many other things are, and we'll get to it in a moment): it reflects actual bodies on the ground--dead people and the people who shoot them.

Just recently, after the Joint List of Arab parties won a record number of seats in the Knesset. After this electoral triumph, the party leader Ayman Odeh published a wonderful editorial in the New York Times--a testament to his very real qualities of leadership. Many commentators reflected on his blend of idealism and pragmatism and on his willingness to support Gantz as Prime Minister (against Netanyahu) but reluctance to join the government. But as a criminologist, I was more drawn to his important and knowledgeable commentary on the problems that really plague the Israeli Arab population:

Our demands for a shared, more equal future are clear: We seek resources to address violent crime plaguing Arab cities and towns, housing and planning laws that afford people in Arab municipalities the same rights as their Jewish neighbors and greater access for people in Arab municipalities to hospitals. We demand raising pensions for all in Israel so that our elders can live with dignity, and creating and funding a plan to prevent violence against women.

We seek the legal incorporation of unrecognized — mostly Palestinian Arab — villages and towns that don’t have access to electricity or water. And we insist on resuming direct negotiations between Israelis and Palestinians to reach a peace treaty that ends the occupation and establishes an independent Palestinian state on the basis of the 1967 borders. We call for repealing the nation-state law that declared me, my family and one-fifth of the population to be second-class citizens. It is because over the decades candidates for prime minister have refused to support an agenda for equality that no Arab or Arab-Jewish party has recommended a prime minister since 1992.What might these resources include? I worry that the facile right-wing and left-wing solutions to Arab-Israeli violence are equally doomed to fail. Let's start with the left wing. About a year ago I sat in a hotel lobby at the ASC annual meeting and talked to a respected and experienced Israeli criminologist, who told me of his Israeli colleagues' reluctance to openly discuss Arab crime rates. It's bad form among left-wing intellectuals to admit that a population that suffers (truly) from overpolicing, overcriminalization, and harsh sentencing, might also be responsible for actual crime on the ground.

This, of course, reminded me of James Forman's Locking Up Our Own. One of the great strengths of the book is that, by contrast to Michelle Alexander and others to whom racial discrimination seemd to be wholly a product of racist policing, racial profiling, and the war on drugs (note that even Michelle Alexander eventually came around to rejecting this facile explanation, albeit without admitting her own errors), Forman's protagonists, black politicians and police chiefs, sought what they thought in good faith to be the best for their communities. Why would Burtell Jefferson embrace stop and frisk? Why would black politicians embrace marijuana enforcement and lax gun laws? Because they were attentive to a community that was really--not just in the putrid minds of white supremacists--ravaged with violence. Perpetrated against black people by black people.

What is often lost in the chatter of those who deem the question "what about black-on-black crime?" racist is the deep understanding that the vast majority of the African American population does NOT commit crime, and that these politicians and cops were operating on behalf of their communities, rather than against them. It could even be argued that this oversight, in itself, is a form of racism. But I see this evasion, the fudging of this truth, everywhere. As a shining example of this, take a look at the NAP commission report on the causes of mass incarceration and how it talks about race and violent crimes:

Note: the relative involvement of blacks in these crimes has "declined significantly". But what about the graph right below this paragraph, which gives you the plain statistics? In the 2000s, when these rates have decreased, black perpetrators are responsible for "only" 50% of the homicides. African Americans constitute about 12% of the population. So, they are overrepresented in the homicide perpetrator population by a factor of four times their percentage in society. Note how my colleagues conveniently avoid mentioning this simple fact, which is literally staring them in the face. Do the numbers for the other violent crimes: also, considerable overrepresentation. And keep in mind that, by contrast to drug offenses (for which we know the official statistics represent differential enforcement, as we know that using and dealing statistics are more or less equal for blacks and whites), for violent crimes official statistics are a far better representation of actual crime commission rates.

Why are my American colleagues not talking about this? For the same reason that my Israeli colleagues don't openly talk about Arab-Israeli crime rates. Because to admit the statistical truth that these groups are overrepresented in the violent crime picture is tantamount to appearing as a racist to your colleagues and friends. Many lefties, both in the academic and in the activist milieus, think that talking about crime rates is tantamount to repeating the racist sayings of the Nixon and Reagan eras about "hoodlums" or "superpredators" or to subscribe to some kind of Lombrosian thinking that "this is how these people are." Nothing could be farther from the truth. There is not a shred of evidence, from the natural OR social sciences, that shows that any racial group is predetermined to commit more crime.

The answer is much more simple. It's become fashionable among some of my colleagues (I see this a lot in the books that came out in the last few years) to criticize liberals and democrats for their contributions to "building prison America" and for their paternalistic assumptions about inner-city black life and the black family. But the bottom line is that, study after study of these supposedly paternalistic, well-meaning white criminologists, has shown that criminality and criminalization basically come from the same place: systematic racism. The same forces that lead entire police departments to structure their stop-and-frisk practices to target African American drivers and pedestrians also account for the poverty, neglect, and lack of legitimate opportunities that produce real violent crime. When people have been oppressed, neglected, dehumanized, relegated to second-class-citizen status for generations, is it any wonder that, in the absence of legitimate opportunities they turn to nonlegitimate ones? And what would be racist or paternalistic about admitting this?

Which is where we come to the other side of the political map. What Forman convincingly argues in Locking Up Our Own is that, faced with the real problems of their community, the policymakers and actors he examined grabbed the only tool available to them: criminal justice and law enforcement. Our recurrence to criminal justice comes, argues Forman, from a lack of imagination: we only have a criminal justice hammer in hand, and therefore everything looks like a nail. Law-and-order types, the likes of which are easy to find in both the Israeli and American governments, are likely to jump on the opportunity to police Arab society (or African-American urban streets, which our caselaw tellingly refers to as "high-crime areas") more aggressively. The outcome of these methods can only be destructive--as it has been, to the detriment to all of us, in the United States.

The truth is that Arab villages and American inner cities do not suffer exclusively from overenforcement or from underenforcement: they suffer from a poisonous, unhealthy combination of the worst of both. Politicized law enforcement, infused with racist stereotypes, will resort to doing less real policing (actually investigating and effectively preventing serious, violent crime) and more harassment and humiliation of people in the streets over minutia. The outcome is that everyone suffers--today you are the repeated victim of humiliating stop-and-frisk and demeaning encounters with a police officer, and tomorrow you're at risk of being the innocent victim of a stray bullet.

Similar things are true for Arab towns and villages. For decades, Arab cities and towns have been shamefully neglected compared with their Jewish counterparts. People don't have basic infrastructure--I'm talking electricity and water services. Arab schools are in shambles in terms of the infrastructure. Workplace and education discrimination are rampant and ugly. With this package of systemic discrimination comes both underenforcement (Arab lives are seen as less worthwhile and thus less efforts are expended to protect them) and overenforcement (every one of my Arab friends can tell you stories of police abuse that will make you shudder.) Is it any wonder that both crime AND criminalization are serious problems, at the same time? And is it a huge theoretical overreach that both come from the same poisoned well of systemic discrimination? How is throwing more police officers to do more humiliating things going to help the crime rates? How can we ever achieve real change with just law enforcement and no real investment in the enormous socioeconomic gaps that birth crime and discrimination in the first place?

Ayman Odeh strikes me as an extremely thoughtful, visionary leader. I hope he can leverage these qualities to deeply comprehend the conflation of two deep truths: that violent crime in Arab society is a real problem, and that more aggressive law enforcement is a terrible solution. And I hope that some of us, in academia and in policymaking, can come to the same conclusions about American crime and law enforcement.